[A presentation for a roundtable discussion on “Tragedy and Epiphany” hosted by the Centre and Library for the Bible and Social Justice, the Alternative Seminary and Bible Remixed. The topic was bringing together the story of the Magi and the slaughter of the innocents in Matthew 2 within the context of the tragedies of this season of Epiphany.]

It is all about the children.

It has always been about the children.

The children aren’t just the collateral damage

in the violent affairs of adults.

They aren’t simply the unfortunate casualties

of the machinations of empire.

No, the children pose a threat to the power structures,

the children hold hope for a future that is unpredictable,

not the controlled future of the empire.

Unless … the children can be socialized into

faithful and docile citizens.

Unless … the children can be held under such bondage

that they can never imagine a different future.

But if that doesn’t work,

if the residential schools don’t manage

to educate (or beat) the Indian out of the child,

well, then there is only one other alternative.

Snuff out the future,

eliminate the threat,

and strike terror into the heart of the population,

by murdering the children.

It’s all about the children.

Pharaoh drowns the children in the Nile.

Herod kills every child under two in Bethlehem.

Matthew knows that it’s all about the children.

Matthew knows that it’s all about the children.

Notice how often he names them:

Where is this child born

king of the Jews?

Go and search diligently

for the child.

They saw the child

with Mary his mother.

Get up and take the child

and his mother by night.

For Herod is about to search for the child.

Joseph got up and took

the child and his mother.

Herod killed all the children.

Rachel weeping for her children.

Seven times.

Child,

child,

child,

child,

child,

children,

children.

It’s all about the children.

It is not for nothing that idolatry and infanticide go hand in hand.

You see, idols have an insatiable appetite for child sacrifice.

Whether it is on the altar of ancient Moloch

or the altars of imperial power,

the ideology of economic growth,

the idols of nation, tribe, race, and religion,

the demons of racism, misogyny, homo and trans phobia,

or the imperative of technological progress,

the children are always offered up to these false gods.

So what do we do as we stand before

So what do we do as we stand before

Rachel weeping for her children?

What do we do, overwhelmed by the wailing

of the mothers of Gaza?

What do we do,

faced with the grief of

missing and murdered

Indigenous women and girls?

What do we do with another school shooting,

another Black man who can’t breathe,

another Latino teenager gunned down on the street

or toddler separated from their parents at the border?

What do we do with all of this anguish?

Well, if Rachel refuses to be consoled

because her children are no more,

then the last thing that we should do

is to offer cheap consolation.

The last thing we should do is insist

that she be consoled,

when she refuses to be comforted.

That would be a form of pastoral violence.

No, if we are to stand with Rachel,

then we must stand with her in that grief.

We have nothing to offer Rachel without tears.

We have nothing to offer Rachel, but to sit with her,

and to share her heart-breaking lament.

. . .

I have buried three babies.

It is the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

Three.

Not the whole population of toddlers of my village.

Not the untold number of children killed in Gaza

and the West Bank over the last 75 years.

Not all of the children murdered in the Holocaust.

Three.

And those three represent the most devastating

pastoral experiences of my life.

And, while I certainly offered no quick consolation for those parents,

and it was important for me to sit with them and simply listen,

– simply bear witness to their pain,

simply weep with these inconsolable parents –

there came a time when words were needed.

Words to name the pain.

Words to stand in the grief.

Words that are never easy,

never ready to hand.

So, sometimes you need to look for those words from someone else.

And just as the story of Epiphany needs the testimony

of marginal figures like some mysterious astrologers from “the East,”

– some discerners of the times, of the seasons, of the stars,

some dubious “wise” men, known for their drinking and frequenting of brothels,

some social disruptors, threats to the royal order –

so might we need to turn to contemporary Magi,

poets, storytellers, songwriters

to help us find the words to describe

the tragedy that permeates our Epiphany.

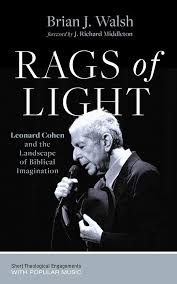

Of late, I’ve been attending closely to the witness of Leonard Cohen.

Of late, I’ve been attending closely to the witness of Leonard Cohen.

Like the Magi of our story this evening,

Leonard discerned the times,

traversed paths of danger,

and knew that he had nothing to say,

if his words did not attend to the tragedy,

the despair, and the horror

of our contemporary lives.

The Magi came looking for a child,

and Cohen also knew that it is all about the children,

and he knew that where there are children,

there is invariably loss and sorrow.

That is why he sings,

I greet you from the other side

of sorrow and despair

With a love so vast and so shattered

it can reach you anywhere.

And I sing this for the captain

Whose ship has not been built

For the mother in confusion

Her cradle still unfilled

(“Heart with no Companion,” Various Positions)

A cradle unfilled.

A cradle robbed.

A cradle, a playground,

A cradle, a playground,

a street, a school, a hospital,

stained in blood,

empty of children.

If there is to be any response to such a tragedy,

if there is to be any “other side

of sorrow and despair,”

then it will need to come

from “a love so vast and so shattered”

that it can hear Rachel’s weeping,

because it knows the shattering of such violence.

Perhaps it could be a love that has danced at Auschwitz:

Dance me to your beauty with a burning violin

Dance me through the panic ’til I’m gathered safely in

Lift me like an olive branch and be my homeward dove

Dance me to the end of love

In the panic of the gas chambers,

can there still be love?

In the horror of slaughter,

can there be any safe gathering?

In the depths of war,

is there an olive branch?

In the domicide, the murder of home,

can there be any homeward dove?

Is this the end of love?

Is this the erasure of love?

Or might the end of love remain?

Might love still be stronger than hatred?

Might the telos of love remain,

even in Rachel’s inconsolable tears?

Isn’t that why she weeps?

And so Cohen sings on:

Dance me to the children who are asking to be born

Dance me through the curtains that our kisses have outworn

Raise a tent of shelter now, though every thread is torn

Dance me to the end of love

(“Dance me to the End of Love,” Various Positions)

Against all odds, against the evidence,

the call to life is inexorable,

and the children are asking to be born.

In the face of the brutality,

the dance of love remains, even behind the curtains

that our kisses have outworn.

In the face of domicide,

the call to homemaking cannot be silenced,

as we continue to raise tents of shelter, though every thread is torn.

. . .

But, maybe this is too quick.

Maybe this is a song that could not be sung at Auschwitz,

just as it could not be sung in Bethlehem or Gaza.

No, this song needed forty years before it could be written.

You see, this artist who has seen the nations rise and fall,

heard their stories, heard them all,

has also seen the future,

and it is murder.

In what some might see as a shockingly “pro-life” sentiment,

Cohen discerns the crises of our times when he sings:

Give me back the Berlin wall

Give me Stalin and St Paul

Give me Christ

or give me Hiroshima

Destroy another fetus now

We don’t like children anyhow

I’ve seen the future, baby:

it is murder. (“The Future,” The Future)

In this oracle of civilizational collapse,

when the false absolutisms of the past will be desirable

to the chaos that is to come,

Cohen returns to the children,

to infanticide, to murder.

But again, maybe even this is too quick.

Rachel already knows about murder.

And we already know about genocidal chaos.

We don’t need an oracle to tell us what we already know.

So maybe we need to move beyond the stark descriptions

and return to inconsolable wailing.

Maybe we need to move beyond discernment

to prayer, to lament, to the questioning of God.

And so the poet prays:

Tell me again

When I’ve been to the river

And I’ve taken the edge off my thirst

Tell me again

We’re alone and I’m listening

I’m listening so hard that it hurts

Tell me again

When I’m clean and I’m sober

Tell me again

When I’ve seen through the horror

Tell me again

Tell me over and over

Tell me that you want me then

Amen, Amen, Amen

I’m listening, Lord.

I’m listening so hard that it hurts.

What does the Holy One have to say?

I’m clean and I’m sober.

I’m no longer numbing the pain,

and I’ve seen through the horror,

so tell me again,

tell me over and over,

tell me that you want me, after all that has happened.

Tell me, God of promise,

is this the way that covenant with you works?

So …

Tell me again

When the filth of the butcher

Is washed in the blood of the lamb

Tell me again

When the rest of the culture

Has passed through the eye of the camp

Tell me again

When I’m clean and I’m sober

Tell me again

When I’ve seen through the horror

Tell me again

Tell me over and over

Tell me that you love me then

Amen, Amen, Amen (“Amen,” Old Ideas)

Tell me again, when the horrors of Auschwitz

have met the genocide of Gaza.

Tell me again, when the goddamned horrors of the camp

have met the blood of the children polluting our land.

Tell me again, if you dare,

tell me again, that you love me then.

. . .

Or perhaps that is asking too much.

Perhaps love is tired.

Perhaps love is worn out.

Perhaps the end of love is … the end of love.

What began in love dissolves into regret.

The joy of creation has reached its eventide.

The tools of humanity are all turned to violence.

The sea so deep and blind

The sun, the wild regret

The club, the wheel, the mind,

O love, aren’t you tired yet?

The club, the wheel, the mind

O love, aren’t you tired yet?

The blood, the soil, the faith

These words you can’t forget

Your vow, your holy place

O love, aren’t you tired yet?

The blood, the soil, the faith

O love, aren’t you tired yet?

Holy One, lover of creation,

covenant Maker,

Faithful One,

in light of all that has happened,

in light of the deep disappointment,

in light of all the bloodshed,

tell me, aren’t you tired yet?

Is that the issue?

Have you reached the end of your love?

Are you worn out, done with it all?

And then our contemporary Magi

pushes it as far as it will go,

with these devastating lines:

A cross on every hill

A star, a minaret

So many graves to fill

O love, aren’t you tired yet?

So many graves to fill

O love, aren’t you tired yet? (“The Faith,” Dear Heather)

What are we to say

when the faiths of the Book,

the people who are rooted in the covenant of love,

have filled so many graves,

and there are more graves to fill?

Isn’t this the exhaustion of love?

Isn’t this the end of love?

Isn’t this the ultimate atheism?

You see, friends,

it has all gone wrong,

and today is not a day

for any hallelujah’s,

neither cold, nor holy, nor broken.

Rachel couldn’t bear it.

And neither should we.

One Response to “Tragedy and Epiphany: It is all About the Children”

Jasper Hoogendam

Children are not yet part of the dominant culture and they are the most vulnerable. Lorin MacDonald stated the same about people with disability. If you aren’t part of the dominant culture you will be left behind. She was recently awarded the Order of Canada for her work in making space for people who are deaf by getting legislation passed that requires Close Captioning. The weak and disabled are always at the back of the line.