Interviewing someone once for a campus ministry position,

I posed two quotes,

and asked the candidate which of the two resonated

most deeply with them.

You’ve got to kick at the darkness

until it bleeds daylight

and

There is a crack in everything,

that’s how the light gets in

The person I was interviewing

recognized the quotes as being respectively from

Bruce Cockburn’s “Lovers in a Dangerous Time”

and Leonard Cohen’s “Anthem,”

and sat with the question for a few moments.

They acknowledged that both are true,

but pastorally they found more hope

in light shining through the cracks,

than in trying to kick our way through the darkness.

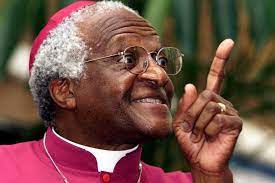

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

famously said,

“Hope is being able to see that there is light

despite all of the darkness.”

Seeing light despite all of the darkness,

in the face of the darkness,

in defiance to the darkness,

and in hope of the light.

Darkness seeks to consume the light,

and so in a time of overwhelming darkness

you need to take an aggressive stance,

kicking at that darkness,

puncturing that darkness,

until it bleeds daylight.

But the fact that darkness can bleed daylight,

assures us that there is light behind that darkness,

and so Mr. Cohen’s insight that the light

shines through the cracks.

Desmond Tutu did not shrink

Desmond Tutu did not shrink

from the machinations

of darkness,

whether in the form of a

racist apartheid regime,

a corrupt ANC government,

oppression of Palestinians,

or LGBTQ+ persecution.

As he used to pray,

Goodness is stronger than evil.

Love is stronger than hate.

Light is stronger than darkness.

Life is stronger than death.

Victory is ours through Him who loved us.

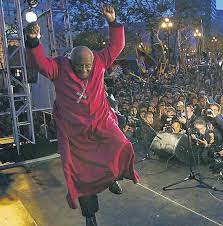

Sometimes he had to

Sometimes he had to

hang on to such

faith by the skin of his teeth,

but more often than not

(at least in public),

he laughed, danced

and preached

his faith in the light

against the odds.

Archbishop Tutu kicked at the darkness,

named the darkness,

shamed the darkness,

took a stance of confrontation

in the face of darkness.

But this was no heroic stance.

This was the stance of faith,

rooted in humility,

radicalized by the gospel,

sustained in sacrament.

Darkness took real form,

in laws, institutions, and violence.

But, as far as

But, as far as

I can understand,

Tutu never objectified the darkness,

never allowed

the systems of darkness

to fully define its perpetrators.

Behind the walls,

behind the constructions of darkness,

in every person,

and every situation,

Tutu could see the light.

The image of God,

the abiding Presence,

the light of goodness and life,

could never be extinguished.

Darkness could never have the last word.

And so the archbishop

would be attuned to the cracks.

He would look for those places

where the machinations of darkness would stall,

where the structures of evil would begin to crack,

and there, as the light would break through,

he would place himself,

welcoming the light,

and pushing those cracks to open just a little more.

Desmond Tutu

October 7, 1931 to December 26, 2021

May he rest in peace and rise in glory.

Postscript on the metaphor of darkness

While Desmond Tutu employed the binary

of light and dark in a way consistent with

biblical tradition, there is an important

voice of correction or reconsideration

that emerges from other black Christians.

I refer you to the provocative poem, “Darkness Goodness”

by the Rev. Jacqueline Daley, posted here.

2 Responses to “Desmond Tutu and the Light”

Stephen Martin

Thanks, Brian. It’s a great loss to the church and to South Africa. At the same time, his witness continues in those who met or heard or read him. My favourite story of his recalls the time when as a young boy he saw Fr. Trevor Huddleston, a white parish priest, bow as he passed his mother, a simple black washerwoman, on the sidewalk one day. Such a thing was impossible in South Africa! He compared it to the way Anglicans recognize the presence of Christ in the sanctuary when the presence lamp is lit. That’s what we are as human beings: presence lamps in the sanctuary of God’s creation. Desmond certainly was that—but most of all in his bearing witness to inextinguishable joy and laughter and delight, which may be the most profound way we image God. (Imagine thinking of God as constituted by inextinguishable joy and laughter and delight). As I’ve remembered my few encounters with him and read today those of others, that’s the common theme: laughter. And God we really need it (and him) now!