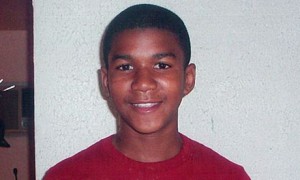

I’ve been wrestling with this all weekend – sometimes crying, sometimes praying. All I keep thinking about is how much he looks like my brother – my sweet, intelligent, amazing brother. I keep thinking that it was society’s job to protect Trayvon. That it shouldn’t have been a dangerous situation for him to be where he was that night. Society failed him. And not only that, in the aftermath, it dissected and destroyed what was left of him – his memory, his character, his denied future – with a viciousness that I could never imagine I’d see in 2013. I’ve been trying to sort out why this has affected me so deeply – I am keenly aware that racism still exists, why should this latest instance trouble me?

So let me tell you a little bit of my story as a Canadian of African descent.

We didn’t have the “you’ve got to work twice as hard, run twice as fast” rule in our home. My mom talked to us about it, but she thought that it put too much pressure on individuals; that it was too easy to become resentful – of how we were born and of how society historically (and currently) treats people of colour. We were always taught to be ourselves, to the fullest, regardless of what society told us we could and could not do. We were taught to be fearless; to laugh at people who questioned our abilities because of our race and gender. We were taught that we should never, ever allow anyone other than God himself to make us question ourselves; to stand up and make our voices heard when people slighted us.

I’ve striven to do this in my life, regardless of how people react. “You’re so sensitive!” “It’s just a joke.” “Stop playing the race card.” “I’m just stating facts.”

I’ve been called a feminazi, an “oreo” (white on the inside; black on the outside), a bitch, a nigger bitch, a militant, a ho. I’ve been told that black is ugly, stupid, violent, evil, less-than. I’ve been propositioned and grabbed and followed and harassed and humiliated by people who think they know me because of what they see, who feel entitled to an opinion of me, entitled to work out their own racial prejudices through me, entitled to touch me, to possess me, to dominate me.

It hurts every single time. Every single instance, big or small. Each time I would call home to my strong, beautiful, amazing mother. And she would say:

“Jess, you just keep doing you. These people aren’t worth your time. You know who you are, don’t let them take that away from you. They don’t deserve it. I am proud of you, you’re an amazing young woman. Good people will see you for who you are and honour that.”

I’d take those words in, I’d hold onto them, and then I’d look around, try to find some small example of society being better. A black woman featured on a mainstream magazine cover. Happy, interracial couples, strolling down the sidewalk on a summer afternoon in the city. A new black face in one of my predominantly White graduate courses. A funny joke from one of my Jamaican friends told me.

Okay, I’d think. Okay. I am not alone. I can keep moving forward. I can keep being me.

But there is something about this case. There is something about Trayvon Martin.

I feel so broken over it.

And the pain just multiplies – first with the unnecessary intrusion of Trayvon’s body for narcotics, then with the denial of charges initially, and then, with the media. Political pundits, commentators, casual observers – Christians, neighbours, classmates, friends. They just attacked. All this hatred and ignorance came pouring out. It is sickening and terrifying.

The world suddenly looks much, much more ominous.

There’s a spirit-crushing dread that haunts us with this new unknown: We don’t know who these vigilantes for justice are. They could be anybody; disguised as your neighbourhood watchmen or your local city councillor or your teacher. We don’t see or hear from them in ‘polite circles’ until some tragic moment, and it’s hard to know if the moment changed them – like an illness that ravages the body – or if they were monstrous all along.

I keep hearing about people who ‘unfriended’ friends on Facebook after the verdict came out. Why? Because the comments. The awful, cruel comments:

“Well, Zimmerman wants to be a lawyer now and good for him. What was Trayvon ever going to do with his life?”

“If Trayvon’s father had given him a curfew, this would never have happened.”

“He should have known not to wear a hoodie.”

On and on, deeper into the vortex of cold irony. How can we feel safe? What ‘small moment’ can calm this storm? I am trying to find it right now, I really am. I’m searching very hard. But I feel unsafe.

Jim Wallis’s “Lament of a White Father” has it right when he talks about hearing, listening, recognizing the pain of others, as a way to affirm them and their experiences. The counter-responses to this verdict – the peaceful protests, the reflective editorials – are important.

But I don’t feel the same hope yet that I have in the past, after a particularly dreadful encounter. I feel, as crazy as it sounds, betrayed. I feel like so many people in the black community have worked and waited and accepted less-than, throughout history and still today, and they deserved to be recognized, heard and acknowledged.

Their pain, our pain, deserved to be honoured in this tragic moment, this perfect, terrible manifestation of every black family’s deepest fear. But they looked in our faces and said: “You’re too sensitive. You’re overreacting. Stop playing the race-card. We’re just stating the facts.”

I don’t know how to respond to that anymore. I feel like I’ve spent my life giving measured, reasoned responses to these kinds of individuals. I now feel like I was shouting into the wind. Maybe this moment has changed me, changed many. Because in all honesty, I don’t know what to do now. When I first called my mother after Trayvon was shot, she said simply: “I can’t talk about this. It’s too much. It’s too close.”

That’s it. That’s the messy, emotional big and the simple, abrupt small of it.

An American activist in Latin America during the eighties was asked why he risked everything to record and release documents to the international community chronicling the violent human rights abuses of both the government regime and private corporations. He explained why he did what he did by saying that he felt a responsibility to “bear witness to injustice.”

Bearing witness to injustice.

I truly hope that people of all races stand up and bear witness, refuse to look away. I think as Christians it’s what we’re called to do, even in times when there is nothing else to be ‘done.’ Recognize it, hear it, listen to it.

I don’t know why it is that questions of race and privilege enrage people. I don’t know why this hell-bent determination to prove that these things don’t exist – that we haven’t done anything wrong – has such a stronghold. I care less every day.

Because whatever the philosophical or theoretical explanations are, it doesn’t change the fact that it’s real. It is real. Real. Real.

Are there deep problems with the Black community? Yes.

Do we in the Black community have work to do? Yes.

But is Trayvon Martin dead? Yes. This is real. Witness this.

14 Responses to “Trayvon Martin and Bearing Witness to Injustice”

jacqueline

Thanks so much Jessica for taking time to write and share your thoughtful lament. I have yet to meet a Black person who is not lamenting over this loss. There is an overwhelming sense of connection to this tragedy that have united Black voices regardless of cultures and distance. Perhaps this is a renewed agonizing awareness that there is no safe place/space for Blacks, especially Black males, who are targets of Black on Black gun violence, profiled as criminals in their own neighborhoods, profiled while driving, walking, profiled simply being Black as “less than”. This puts every Black mother with sons on renewed alert and anxiety of the dangers that awaits their sons while Black. Thanks again for sharing.

Jessica

Thanks for reading, Jacqueline (and it’s good to hear from you!). I absolutely agree – something about this case, Black people all over are grieving it deeply. There’s a sense of: “What now? How much louder can we shout for justice?” Something has to change – we shouldn’t feel this terrified in our societies in 2013. We just shouldn’t.

Kyle

I am confused on what the injustice is? How is this a case of racism. I am all for being against racism, but this doesn’t shout out racism or injustice to me.

B. Walsh

Kyle, I wonder if the comment below from Sylvia, might answer your question.

But let’s think about this for a moment: An unarmed black child was killed by an armed white man and there are no punitive consequences for this. Can anyone really think for half a minute that if the race of the two people involved was reversed, that we would have had the same verdict? Would the same verdict have been delivered if the trial happened in a part of Florida that had a larger black population?

And then there is the question of the justice of any ‘stand your ground’ law.

But when it comes right down to it, Ms Brown’s piece gives voice (as does Jacqueline’s comment) to the fear that I do not live with in my society because of my skin colour. That fear, that legitimate, real fear, that my black neighbours live with day in and day out, is injustice.

To such injustice, Ms. Brown must give witness.

Thea

Hey Kyle,

If you’re interested in this topic, I’d suggest a little reading on “Implicit Associations.” Harvard has a Project Implicit website that has tests and info. Anyhow, what they’ve found is that, while most people today aren’t explicitly racist, there still are deep levels of bias against black people amongst 70% of test takers. Even 50% of black people who take the test find implicit biases against black people. Now, the good thing is that implicit biases can be overcome by deep consideration, slow decision making, etc.

The problem comes when decisions have to be made in a short period of time (like when deciding whether to shoot). So, a psychologist at U North Carolina studied whether there was an implicit bias to perceiving a gun when paired with a black face vs a white face. The answer was basically as the time pressure increased, the likelihood of assuming black face=weapon, white face=hand tool increased.

It’s quite possible to call this racism without calling Zimmerman (or the police, or the prosecutors, or the jury) a racist. Racism is deep inside most of us, and if we aren’t critically self-reflective, it will play out in our day-to-day lives. Sometimes subtly, sometimes with severe consequences.

Sylvia

Jess, thank you so much for writing this. It isn’t just Black people who are stricken by this verdict; many of us who are white are similarly shaken and grieving. With this difference: we aren’t worried about this happening to our children, happening to us. Which means, however, you slice it, that we are in a privileged position. Your anxiety and dread is not shared by us in the same way. That said, many of us deeply love our Black friends (I’m talking about you, sister). And so we do have anxiety and dread for the those whom we love and for the communities that we are a part of. But, more than that, we in the white community also need to acknowledge that we have deep problems, that we also a lot of work to do, that we should be engaged in deep repentance, and that we also need to bear witness, not just to the fact that Trayvon is dead. But to the fact that we are complicit. As U2 said, “I held the scabbard while the soldier drew his sword.” Maybe we need to acknowledge that we held Trayvon down while Zimmerman shot his gun. And repent. And pray that love will come to town–to our towns and streets.

Susanne McKim

Jessica, thank you. Your reflection and questions and challenges, framed with such vulnerability, has opened the floodgate of tears and lament for all of us. You’ve given us permission to weep with the injustice and the uncertainty so that we can weep out our rage without being disempowered by it.

Sylvia and Brian are so right – we white people cannot truly know this reality. It is not our experience. So with our corporate guilt and repentance, we weep with you. And we seek strong voices for guidance as to how to give flesh and bones to that repentance.

One of the major lessons in this tragedy is how mainstream media controls the tension by forming images of why the outcome makes sense – seeking to weave rationalizations about the event into our thinking before the verdict comes down. Dear God, give us the true voices of justice.

Susanne

Jessica Brown

Thank you, Sylvia, for your words of support. I mean it when I say that every word of humility and encouragement that I’ve heard in the last week has been a small blessing, a reminder that maybe we’re not alone in the world, screaming into the wind.

Kyle – I want to echo what Brian pointed out and add a few thoughts, as you aren’t the first one to question “where the racism is.” This isn’t an attack; I really just want to help you understand, if I can.

The narrative coming from Mr. Zimmerman’s defenders has been very careful to avoid the aspects of this case that very clearly speak to the implicit and explicit racism inherent in the legal system. Many in the general public have been willing to believe this editorializing because its the same song that has been playing for decades: Black men have a tendency toward crime and lawlessness, which is why they make up a disproportionate number of inmates in the prison system.

What is often left out, however, is any form of contextualization. The benefit of the doubt is absent, and in its absence is a pervasive and deep-running suspicion that put so many black people in the impossible situation of trying to disprove the ‘facts’. So, for example, marijuana laws disproportionately target Black and Hispanic men and level heavy sentences (heavier than their White/wealthier counterparts). ‘Technically’ you have the ‘facts’ to back up a claim (“Black men are criminals – look how many of them are in jail!”) which can be ‘technically’ proven (“Look at the stats!”). But in reality, these are incredibly misleading, inaccurate and in actuality, racist. And being a minority (or poor, or ‘illegal’, or otherwise disenfranchised), you have even less power to fight it (especially because, in the eyes of the law, they *are* guilty).

Trayvon was put in an impossible situation because of the underlying narrative of black criminality in this society. This is the context in which Mr. Zimmerman – who has had a history of this kind of profiling – began to follow Trayvon. Questions such as: why was Trayvon out so late, anyway? Why did he confront Mr. Zimmerman at all? Why didn’t he just run? have put the onus on the victim, however, to explain why he was there to begin with.(What else should he have done to save his life? I promise you: if he had run, Mr. Zimmerman would have chased him. Why run when you have nothing to hide, right?). The acceptance of the argument that “I’m not racist, I was just defending myself”, implicitly (and in some cases, explicitly) endorses the idea that Trayvon did not belong there (outside, in the evening, in a gated community, his own neighbourhood); that Trayvon – who did nothing to provoke Mr. Zimmerman – owed him an explanation for his presence; that Trayvon did in fact ‘look suspicious’ and could be blamed for looking that way. It taps into that old notion that a different standard of public presence exists for Blacks. It does this because it offers a presumption of innocent intent (one that most assuredly would not have been offered to Trayvon, had the situation been reversed) on the part of George Zimmerman, even though such innocent intent is dubious at best: Mr. Zimmerman had a gun (whereas Trayvon did not), knew he had a gun (where, again, Trayvon did not),failed to follow the clear advice of the authorities, cocked and loaded the gun before exiting the vehicle, instigated the fight, had no witnesses to corroborate his story definitively, has a history of racial profiling, changed his testimony multiple times, benefitted from a carelessly inspected crime scene, as well as friends in law enforcement and, finally, ultimately, killed Trayvon Martin (not the other way around).

Jessica

…sorry, I seem to have lost the other part of the comment.

CONTINUED:

In spite of all of this, George Zimmerman walked. Not only did he walk, but now we’re being told that this clear case of racial profiling and the obvious double-standard had nothing to do with race; that we are ‘playing the race card’ and ‘buying into media hype.’ This time, the Black community – and now other communities in solidarity with the Black community – are refusing to accept that narrative. We are calling it by its name – racism – and not backing down. But the backlash from people who want the status quo to remain is powerful – and painful. Because it denies that our experiences are even real, let alone valid. That’s why having people listen to our stories – even when they can’t relate, as Sylvia so beautifully and movingly explained – is so important. It says: we hear you, we love you, we ache with you. That’s why I wanted to share my thoughts, why so many people of colour are sharing their thoughts and experiences right now. We need to hear those words: we hear you, we love you, we ache with you.

Thea

More than a century ago, WEB Dubois opened “The Souls of Black Folk” with these lines:

In the midst of the fear and the anger, the unrelenting grief, there’s a dull resignation that, in 110 years, the essential question for us hasn’t changed. My skin, my very self, is the problem. How does that feel?

Erin

Dear Jessica, and all those who have also borne witness to this tragedy – thank you for the vulnerability, courage, precision and – yes, even – hope of your words. As a white middle-class woman, I can only echo Sylvia’s admiration, gratitude, repentance and grief. May our eyes stay open, our voices be strong, and our steps be unified in justice and compassion. For what it’s worth, I do believe that your testimonies have “done much” in a time when there seems like nothing to do – they are transformative and compelling, yet astonishingly patient and gracious.

Jessica

Dear Erin,

Thank you for reading and for your lovely response. In the last few days, as people have been reacting to this story (and the testimonies that have followed it), I’ve been blown away by the depth of compassion and honesty that some people outside the Black community have displayed. I’ve found it to be something of relief, that people have responded so thoughtfully and respectfully. I admit, I got a lump in my throat reading your comments, and Sylvia’s and Brian’s. I don’t know what I expected – but I was deeply moved.

It’s funny: I’ve been reading some responses by others in the Black community, and been struck by how many people have voiced out loud just how much prejudice (whether explicit or implicit, as Thea perfectly defined) still hurts, at an individual level. You get the sense from these ‘confessions’ that many people of colour supress the pain on a daily basis, because fighting it all the time, constantly trying to get people to believe you, to not see you as “a problem” can wear you down. Black people become used to the status quo, and uncomfortably adjusted to how much, how deeply it hurts.

But having people acknowledge this takes a little bit of that burden off of the individual and the community. Gives you a little more strength to keep standing up to this world that tells you, in a thousand little ways each day, that you are a problem. So, again, thank you. 🙂

Ann

Hey Jess,

Thank you for this. I’ve read your piece more than a half dozen times over the last few days. It took me so long to respond because I don’t know what to say. I’m baffled. I’m grieved. I’m feeling kinda paralyzed, wondering my part in all this. How does such blatant racism happen while the world watches? Your piece has been a grounding way for me (to try) to wrap my head around what happened with Trayvon Martin. Grounding, in part, because it’s not grounding. Thank you for not having easy answers to try making sense of something so senseless. I am grateful for you and for all the dear friends who commented who can point out the little moments of grace and hope in the midst of all this, while still being truly angered that this happened. In solidarity…