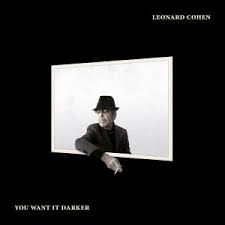

On March 12 I preached twice on the story of the Samaritan woman at the well. The first sermon was addressed to St. Margaret’s Church in South Etobicoke, Toronto and has already been posted here. In the evening, I returned to the Church of the Redeemer to preach on the same story within the context of a very different community, and as part of a Eucharist that employed the music of Leonard Cohen. So what happens if you bring Leonard along to the well for this exchange between Jesus and this marginalized and oppressed woman? The texts were again John 4, with the addition of Isaiah 42.1-4, 9.

The Cohen songs played during the service, and used in the homily were:

“Show me the Place”

“Amen”

“If it be your will”

“Suzanne”

“Treaty”

“Heart with No Companion”

I wonder how she felt,

carrying her empty water jug

out to the well

in the noonday heat.

She hadn’t come in the coolness of dawn

with the other women because

her presence wasn’t welcome with them.

Was she thinking of how heavy

that jug was going to be on the trek home?

Was she bitter that her demeaned status

in the community was what had led to her isolation?

Was she angry, thinking of the men in her life,

including the one back at home waiting for

his damn water?

Were there tears in her eyes,

or had they dried out after

so many years of disappointment?

Was she exhausted,

tired and angry all the time?

I wonder how she felt,

carrying her empty water jug

out to the well

in the noonday heat.

And I wonder how she felt

when she saw that there was a man at the well.

A solitary man and a woman alone

was dangerous enough.

But this was an enemy.

This was a Jew,

who would have had even deeper contempt

for this woman,

then had her neighbours in town.

They viewed her as unclean

because of all the men.

He viewed her as unclean

because she was a Samaritan.

And imagine her shock when he spoke to her.

Imagine her shock when he asked for a drink of water.

Imagine her shock that he would risk touching the same

jug as she, an unclean woman of Samaria.

And I wonder about the tone of her response.

“How is it that you, a Jew, ask a drink of me,

a woman of Samaria?”

Was this incredulity?

I can’t believe that you are addressing me.

Or was it more defiant?

How dare you address me!

When he replied with an offer of living water,

it could have come across as arrogance.

“I don’t need your water (even though he had just asked for some)

because I’ve got a deeper spring of water available.”

But I kind of doubt it.

His offer of a water that will quench her deepest thirst,

was immediately received as an invitation that she is prepared to take.

That is something for a woman whose invitations from men

had seldom resulted in any good in her life.

I mean, I could imagine her being a lot more cynical.

I could imagine her being totally unreceptive

to any any offers from a man,

even if it was of something strange like living water,

to any invitation to a life beyond the one

that had her walking to that well by herself,

day after day after day.

So maybe it is appropriate that we set up this gospel reading

with Leonard Cohen’s “Amen.”

We were preparing to hear the good news,

we were setting things up to hear anew about the love of God,

and we invited Leonard Cohen to set the stage.

Tell me again

Tell me again

When the filth of the butcher

Is washed in the blood of the lamb

Tell me again

When the rest of the culture

Has passed through

the eye of the camp

Tell me again

When I’m clean and I’m sober

Tell me again

When I’ve seen through the horror

Tell me again

Tell me over and over

Tell me that you love me then.

Amen, amen, amen.

In the face of all of the evidence,

in the face of our unconsolable loss,

in the face of our broken hearts,

tell us again,

that we are beloved.

You see, if anything like the Christian gospel is to be believed,

if we are to hear anything like good news,

if we are to be able to enter into a story like this meeting

of Jesus and a Samaritan woman at a well,

then this story, this good news, needs to speak into

our own world of betrayal, brokenness, and disappointment.

I wonder if she had any of that going on in her heart,

during this conversation.

Because if she didn’t then Jesus made a point

of rather indelicately bringing the conversation

back to the realities of her life,

the realities that had her at that well,

in the middle of the day,

alone.

Jesus offers her living water

that will not only quench her deepest thirst,

but will be an eternal spring deep within her soul;

and she says “Amen, I want that water,”

so Jesus tells her to go and call her husband and come back

to get that water.

Prying? Probably.

Insensitive? Well, no.

In fact, this was deeply sensitive.

She replies,

“I have no husband,”

and Jesus answers,

“you are right in saying,

‘I have no husband’;

for you have had five husbands,

and the one you now have

is not your husband.”

And then he repeats himself,

“What you have said is true.”

And again, the question is tone.

Is this a “gotcha” moment?

Does he say this in an accusing voice?

Or is there a shared sorrow here,

a moment in which Jesus acknowledges

that this is a woman who has been bounced from man to man,

married, divorced, married, divorced, over and over again,

and she has had no say in the matter.

Here is a woman who has been used and abused,

exploited and discarded,

and that is why she is at this well alone

in the heat of the scorching noonday sun.

It is as if Jesus is saying,

I know the horror that you have lived through,

I know that you have been discarded by one man after another,

but I need you.

And I know that love has never meant more

than abuse in your life,

but I love you.

I know that you are a victim,

that you are not responsible for your abuse,

but, against all the evidence,

I tell you that you are a beloved child,

and living water is on offer to you.

And I can imagine this woman replying,

Tell me again

Now that I’ve been to this well

And you’ve taken the edge off my thirst

Tell me again

We’re alone and I’m listening

I’m listening so hard that it hurts

Tell me again

Now that I’m clean and I’m sober

Tell me again

since I’ve seen through the horror

Tell me again

Tell me over and over

Tell me that you love me then

And, I don’t know, but maybe Jesus replies,

Amen, amen, amen.

So be it. You are beloved.

Or, what happens if we allow Cohen’s achingly beautiful prayer,

“If it be your will” to resonate with this story?

What happens if we put this prayer on the tongue of this woman?

What happens if this woman of deep rejection and loneliness,

this woman who has no one to talk to

musters up the courage to speak such words

to this amazing man at the well:

If it be your will

If it be your will

that I speak no more

and my voice be still

as it was before

I shall abide

until I am spoken for

if it be your will…

only to find that she is spoken for.

She is called, invited to raise her voice.

What happens if we hear this tormented women pray,

Let your mercy spill

on all these hearts in hell,

if it be your will

to make us well …

only to have healing waters offered to her,

waters to quench her thirst,

waters to extinguish and transform the hell that is her life.

And what happens,

if a woman who has only known intimacy as abuse,

and only known marriage as bondage

until being thrown out once again with the trash,

dares to sing,

And draw us near

and bind us tight

all your children here

in their rags of light

in their rags of light

all dressed to kill

and end this night

if it be your will …

only to meet a man at this well

who has touched her perfect body with his mind.

Who has drawn her into an intimacy of love

without exploitation.

Who has invited her into a covenantal binding

that will set her free.

And who will end the night of her oppression,

the night of her suffering and abuse,

the night of her silencing and rejection,

with the dawn of a new day,

perhaps even a resurrection day.

And so this lonely and rejected woman of Samaria

returns to her town,

returns to a place where no one really wants to hear her voice,

no one really thinks that she has anything to say,

and certainly no one is expecting any good news

to come from this woman of rejection,

and she speaks.

She has been spoken for.

Jesus has spoken for her,

and having found her voice,

she goes to the town square and proclaims:

“Come and see a man who told me everything

I have ever done! He cannot be the Messiah, can he?”

Why does she think that Jesus might be the Messiah?

Did he accomplish any miracle at the well? No.

Was it because of his profound teaching and offer of living water?

That’s not what she says.

Was it because he had so beautifully broken down

the gender, religious, ethnic and cultural barriers of the day?

That’s all true, but that isn’t the reason that this woman offers.

He just might be the Messiah, she surmises, because

“he told me everything I have ever done.”

John obviously thinks that this is incredibly important

because he repeats the assertion a couple of lines later.

And it is clear, that she was not burdened with shame

at what Jesus had said.

His accurate observation did not

weigh her down in silence.

Rather, naming her oppression was liberating.

She had found her voice,

she had found the courage to speak into her community,

she had good news to share,

even if she was such an unlikely source of any such news.

Now remember, all Jesus had said was that she’d had five husbands,

and the man she was now with was not her husband.

And yet, that description of this oppressed woman,

got to the heart of who she is.

The tone was not one of accusation,

but of loving and sorrowful acknowledgement.

In naming the repetitive betrayals of her marital history,

Jesus told her that he understood,

he knew that,

she had been discarded and used;

she had been an object of desire,

and an object of shame;

she had been excluded, marginalized,

and was deeply, deeply lonely.

This man at the well,

saw all of that and named it

in such a way that she began to experience healing.

If the Messiah would be the one who

would not break a bruised reed,

or snuff a dimly burning wick;

if the Messiah would be the one

who would bring forth a healing justice;

if the Messiah would be the one

who would bring liberating newness

in the face of the same old oppression,

then maybe, just maybe,

this intriguing man at the well

might be the Messiah.

And I wonder again,

if words from Leonard Cohen

might have resonated with her message.

What happens if we hear this woman

What happens if we hear this woman

singing to her neighbours:

I greet you from the other side

Of sorrow and despair

With a love so vast and shattered

It will reach you everywhere

Isn’t that where she is,

after this transformative encounter with Jesus?

On the other side of sorrow and despair.

And while she might not have anticipated

the shattering of the love of Jesus on the cross,

she certainly knew of a shattered love in her own life,

a love now rekindled by Jesus that could

reach into the depths of anyone’s sorrow.

And could you hear this woman whose life

was so full of frustration, confusion,

and unfulfilled hope, proclaim that she is singing,

“for the heart with no companion”?

Didn’t she know all about that?

She had never had a true companion.

Her heart was left companionless,

rejected, without a friend.

And can’t you hear these words

coming off the tongue of this woman?

Through the days of shame that are coming

Through the nights of wild distress

Tho’ your promise count for nothing

You must keep it nonetheless

Not only did she know all about days of shame,

not only had she experienced countless nights of wild distress,

she could have anticipated that such shame

and such distress were what was in store for her community.

Not only had she experienced such shameful treatment,

she likely could have seen that the ongoing Roman military occupation

of Samaria could only paint a future of increasing distress.

How the men had treated her

was the mirror image of how empires

treated their vanquished subjects.

The violent dynamics of occupation

are the same.

And having lived through empty promise after empty promise,

she knows that without a renewed

and deepened faithfulness to covenant,

without being held in loving intimacy

and bound tightly in covenantal promise,

there would be no hope.

So, “tho your promise count for nothing/

you must keep it nonetheless.”

And what happens?

The village that had rejected this woman,

follows her back to Jacob’s well

to meet Jesus themselves.

There is something about her testimony,

as simple as it was,

that inspired folks to want to meet Jesus.

And it is amongst despised Samaritans

that Jesus is welcomed as nothing less than

the Messiah and the Saviour, not just of Samaria,

nor of Samaria, together with Judea and Galilee,

but of the whole world.

So we move from one unheard of thing

– a Jewish man talking to a Samaritan woman,

to another unheard of thing

– a Jewish rabbi and his disciples enjoying

hospitality for a couple of days in a Samaritan village.

And it all happens at a well.

It all happens at a gathering place

where life-sustaining needs are met.

It all happens because Jesus

honoured and respected this woman.

It all happens because he names her pain,

and refuses to cast shame upon her.

It all happens because

he touched her perfect body,

not with greedy hands,

but with his mind.

It all happens because there is a coming together

in spirit and truth,

in love and respect.

It all happens because Jesus told her

everything that she had ever done,

but did not reduce her to that

oppressive past.

Jesus refused to let the story

of loneliness and rejection

be the last word on

this beloved daughter’s life.

Jesus named what her life had been,

and in offering her living water

invited her to a life of joy, rather than sorrow.

And Leonard Cohen understood all of this

better and more profoundly than most.

From the beginning to the end,

Cohen had been dealing with Jesus.

From “Suzanne” on the first album to

From “Suzanne” on the first album to

“It Seemed the Better Way” and “Treaty”

on the album released weeks before his death,

Leonard had a love affair,

and an ongoing argument with Jesus.

Maybe that’s you too.

Maybe that’s why you are here tonight.

Maybe you think that listening to Cohen in a church

just might make sense out of both Leonard and Jesus.

Maybe Jesus has, in some way,

touched your perfect body with his mind.

A we gather for the Eucharist you will hear the band sing

words from the chorus to the second verse of “Suzanne.”

Referring to Jesus, Cohen sings,

and you want to travel with him

you want to travel blind

and you think maybe you’ll trust him

for he’s touched your perfect body with his mind

Maybe you’ll trust him.

Leonard wasn’t prepared, and maybe we aren’t prepared

to jump into this Jesus thing with both feet

like the Samaritans did.

But in the 1993 concert tour, Leonard sang,

And you want to travel with him

you want to travel blind

and you know he will find you

for he’s touched your perfect body with his mind

From maybe you’ll trust him to a confidence,

not necessarily in one’s own faith,

but in the commitment of Jesus to seek us out,

to being found, as our Samaritan sister was found.

And then, during those late tours

And then, during those late tours

towards the end of his life, Leonard began to sing:

And you want to travel with him

you want to travel blind

and you know you can trust him

for he’s touched your perfect body with his mind

No longer “maybe you can trust him,”

but a surprising affirmation of faith,

“you know you can trust him.”

There is a remarkable certainty in those lines.

There is a sense of coming home,

a coming to terms with Jesus,

at least for the moment of singing those lines.

So friends, whether you think maybe you can trust Jesus,

or you have a sense that somehow, like the Samaritan woman,

you have an intuition that Jesus can find you,

or you are more secure and you know you can trust him,

or, indeed, if you aren’t sure about any of this whatsoever,

we’re going to set the table of Jesus in a minute.

Nothing too elaborate.

Just a little bit of bread and a sip of wine.

And you are invited to the feast.

The Samaritan woman was thirsty

and Jesus offered her living water.

If you are hungry,

like she was thirsty,

then come and share in the bread of life,

and the cup of salvation.

Amen.