“A voice is heard in Ramah,

weeping and great mourning.

Rachel weeping for her children

and refusing to be comforted,

because they are no more.” Matthew 2.18

“As Jesus was leaving the temple, one of his disciples said to him,

‘Look, Teacher! What massive stones! What magnificent buildings!’ ‘

Do you see all these great buildings?’ replied Jesus.

‘Not one stone here will be left on another; every one will be thrown down.” Mark 13.1–2

September 30, 2021, is Canada’s first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

The day arrives in the wake of a summer of grief and anger, of burning churches and unearthed crimes, the wounds of which—for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, Christians and non-Christians—are still fresh. In the spirit of the day, and in the light of the Gospels, I would like to explore some of the truths that I believe the events of the past summer obliges Christians, in Canada and around the world, to confront and speak.

As of September 16, 2021, 1,802 unmarked gravesites—mainly those of children—have now been found at Canadian residential schools.

As of September 16, 2021, 1,802 unmarked gravesites—mainly those of children—have now been found at Canadian residential schools.

215 at the Kamloops Residential School, on the lands of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation in British Columbia—a school run primarily by the Catholic order of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate.

751 at the Marieval Residential School, on the lands of the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan—run by various Catholic missionary orders from the late 1890s to 1968.

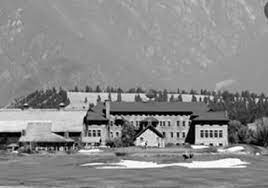

182 at the Kootenay Indian Residential School, on the lands of the Aqam band of the Ktunaxa First Nation in British Columbia—run by the Catholic Church ran from 1912 to 1970.

182 at the Kootenay Indian Residential School, on the lands of the Aqam band of the Ktunaxa First Nation in British Columbia—run by the Catholic Church ran from 1912 to 1970.

And hundreds more at other locations in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and the Northwest Territories.

Similar discoveries are expected at many more of the 138 former residential school sites in nearly every province and territory of Canada.

The Canadian government’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission has characterized the aim of the residential schools as “cultural genocide.” These discoveries remind us—as the other discoveries to come will remind us again—that the largely church-run system, in its coerciveness, neglectfulness, and abusiveness, was not just culturally but literally murderous.

The Canadian government’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission has characterized the aim of the residential schools as “cultural genocide.” These discoveries remind us—as the other discoveries to come will remind us again—that the largely church-run system, in its coerciveness, neglectfulness, and abusiveness, was not just culturally but literally murderous.

In response to these discoveries, at least 56 churches (as of July 29) have been set on fire or vandalized: windows smashed, facades or statues painted red or orange or covered with red handprints or footprints, or graffitied with text such as “Charge the priests” and “Our lives matter” or the numbers “215” and “751.”

In response to these discoveries, at least 56 churches (as of July 29) have been set on fire or vandalized: windows smashed, facades or statues painted red or orange or covered with red handprints or footprints, or graffitied with text such as “Charge the priests” and “Our lives matter” or the numbers “215” and “751.”

Many of the damaged or destroyed churches are located on Indigenous land; most but not all of them are Catholic; and some have no direct connection to the residential school system.

Indigenous leaders have generally condemned acts of arson or vandalism as, in the words of one daughter of a residential school survivor, “not in solidarity with us.” Other prominent Canadians, though, have characterized church arson as “understandable” or tweeted “Burn it all down.”

The destruction or damaging of churches, for any Christian, is bound to be painful. The discovery of thousands of graves of murdered children, anonymous and un-honoured, is—for any human being—bound to be much more painful.

I believe that Christians can make sense of these twinned causes of pain—and begin to understand, acknowledge, and lament our responsibility for them—by reflecting on two stories from the Gospels.

The stories come from different books and opposite ends of Jesus’s life. Viewing them in the light of this summer’s events, however, reveals how they are connected and how they resonate with those events.

Taken together, these stories describe what happens, in Jesus’s time and our own, when religious institutions join forces with and serve the cause of empire: what happens to the people who religious institutions help empire subjugate, and what happens to the religious institutions themselves.

In Chapter 2 of the Book of Matthew, King Herod, the Roman Empire’s puppet ruler of Judea, hears from magi arriving from the east that the “king of the Jews” has been born.

Matthew writes that Herod is “disturbed” by this news—understandably so.

The “king of the Jews”—or, as the term could also be rendered, “king of the Judeans”—now reportedly existing among Herod’s subjects is not just a rival claimant to Herod’s own title. He is the Messiah, the prophesied liberator and redeemer of Israel, who is expected to free his nation from the foreign imperial power that now subjugates it—the foreign imperial power whose client Herod is.

Herod learns from the “chief priests”—who, the gospel implies, are just as disturbed as Herod, since the Messiah threatens to supplant their authority too—that the king of the Jews is prophesied to be born in Bethlehem. He dispatches the magi there to find the child for him. When they wisely do not report back to him, Herod, enraged, gives orders “to kill all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity who were two years old and under.” Matthew describes the consequences of this atrocity by quoting the prophet Jeremiah:

“A voice is heard in Ramah, weeping and great mourning, Rachel weeping for her children and refusing to be comforted, because they are no more.”

“A voice is heard in Ramah, weeping and great mourning, Rachel weeping for her children and refusing to be comforted, because they are no more.”

The grief of mother Rachel for her children, taken away and murdered by the agents of her people’s colonial rulers, is the grief of thousands of Indigenous people, for well over a hundred years, at the similar crime meted out to their children—and for a similar reason.

Like Herod and his chief priests, the colonial rulers in Canada, and the religious authorities who aligned themselves with and benefitted from that colonial rule, perceived the autonomous traditions, the independent identity and existence, of the people whose land they occupied as a threat to their power.

The settler-colonial Canadian state desired to obliterate Indigenous people as distinct nations, just as Herod desired to quash his Judean subjects’ hopes for truly independent nationhood.

And in both cases, the agents of empire set about eliminating the possibility of their subjects’ cultural or political autonomy by deliberately targeting their subjects’ children: the ones who in the future might otherwise preserve or reestablish the autonomy of these subjugated nations.

Herod actively murdered the children of Bethlehem.

The murder of the children of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, and of Cowessess, and of Ktunaxa, and of innumerable other Indigenous communities was not quite so deliberate or overt.

However, a system in which the death rate for enrolled students at residential schools was as high as 25 per cent can only be described as pedicide, the murder of children.

Canada’s residential schools were a drawn-out, decades-long Massacre of the Innocents.

And as the magnitude of this crime was revealed anew by the discovery of over a thousand unmarked graves, the grief and rage of Rachel weeping for her children—her refusal to be comforted or appeased, because they are no more—broke out afresh this past summer among both Indigenous communities and many of their non-Indigenous compatriots, and was vented in part upon churches—all too many of which were, like Herod’s chief priests, implicated in the crime.

Which brings us to the second Gospel story.

In Chapter 13 of the Book of Mark, we find Jesus in Jerusalem, where he is shortly to be accused, tried, convicted, and executed by the Roman imperial authorities and their cats’-paws among the Judean religious establishment.

Jesus has spent most of the previous two chapters preaching in the Jerusalem temple and debating with its institutional leadership. As he departs the temple at the start of Chapter 13, one of his disciples calls his attention to the edifice’s size and beauty: “Look, Teacher! What massive stones! What magnificent buildings!”

Not only is Jesus apparently unimpressed; he responds with a dark prediction of this magnificent house of worship’s impending destruction:

Not only is Jesus apparently unimpressed; he responds with a dark prediction of this magnificent house of worship’s impending destruction:

“Do you see all these great buildings? Not one stone here will be left on another; every one will be thrown down.”

A similar fate to that which Jesus foretells here for the Jerusalem temple has now befallen defaced or burned churches across Canada, and for a similar reason: the Church’s complicity, like the temple, with empire.

The chapters of Mark that lead up to Jesus’s prediction of the temple’s downfall are filled with glimpses of the temple authorities’ cowardice, greed, and hypocrisy: their fear of the people to whom they supposedly minister, their unwillingness to defy or even risk any disturbance to the imperial power structure into which they have been assimilated, their love of wealth and privilege, and the exploitative covetousness with which they extract the money they use to adorn and glorify themselves, even or especially from those least able to afford it.

In addition, as Mark’s original readers would surely have known, the Jerusalem temple had been rebuilt and refurbished, in the grandiose manner that Jesus’s disciples so admired, by none other than the same King Herod who was responsible for murdering the children of Bethlehem.

Rebuilding the temple was Herod’s attempt to win the favour of his Judean subjects and advertise his own piety, but the scale and extravagance of the project also served to demonstrate his wealth and power.

Herod even left a direct sign of his adherence to the empire, and of his renovated temple’s connection to it, on the very gates through which Jesus would have entered and exited the temple: a Roman eagle.

Like Herod’s temple, the Church in Canada is deeply bound up with imperial subordination and violence.

And like Herod’s temple, the Church in Canada grew rich and adorned itself magnificently while remaining bound up with this imperial violence. It continues to grow rich and adorn itself magnificently today while avoiding a real reckoning with or recompense for that violence.

In a 2005 agreement, the Catholic Church in Canada promised $25 million in reparations to survivors of residential schools. The Church has claimed to only be able to raise $3.9 million of that promised payment; at the same time, however, it has raised a total of nearly $300 million for its own building projects nationwide.

At the end of Mark Chapter 12, just before one of his disciples extols the temple’s “massive stones” and “magnificent buildings,” Jesus calls his disciples’ attention to the donations to “the temple treasury” that fund this magnificence, including not just “rich people” giving “large amounts” but also “a poor widow” who gives “two very small copper coins, worth only a few cents”—which, Jesus notes, is “all she had to live on.”

This passage has traditionally been read as praising the widow’s sacrifice. In the light of the disdainful prediction of the temple’s downfall that immediately follows it, though, it is better interpreted as a condemnation of a religious institution that glorifies itself by exploiting the piety of the poor—in effect, by robbing from them.

In a similar way, the massive stones and magnificent buildings of churches across Canada, raised by money that should have gone towards restitution for the abuses the Church helped to perpetrate, represent a theft from people subordinated by empire.

This religious architecture, as much as that of Herod’s temple, has become part of the imperial edifice.

Jesus’s prophecy of the temple’s destruction was fulfilled within a generation. In 66 CE, the Judean people rose in revolt against the Roman Empire, and in 70, a retaliatory Roman army destroyed most of Jerusalem, including the temple.

The destruction of churches across Canada happened for a superficially very different reason. Their stones were thrown down by protesters against imperial violence, rather than by perpetrators of it.

Fundamentally, though, both acts of destruction spring from the same root. Both occurred because the religious institutions in question became enmeshed with empire, and consequently became caught up in the anger and violence that empire creates.

The Jerusalem temple would not have burned had not imperial injustice, exploitation, and atrocity sparked a fire in the empire’s subjects like that which, this past summer, galvanized many Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, to “Burn it all down.” And as Mark’s gospel suggests, the greed, corruption, and complicity of the temple authorities themselves helped kindle that fire, just as the involvement of various Christian denominations in the residential schools has kindled anger and outrage.

When read in the light of what took place in Canada in the summer of 2021, then, chapter 13 of the Gospel of Mark, together with chapter 2 of the Gospel of Matthew, are saying something that may be hard for Christians to hear but is necessary, indeed imperative, for them to heed.

The Christian Church has not just abetted but perpetrated a massacre of innocents in Canada.

And Jesus’s prophecy of the destruction of the temple—rebuilt by the ruler who carried out the biblical Massacre of the Innocents, and complicit with the empire on whose behalf that ruler was acting—is a warning to us that the destruction of churches in response, while by no means to be encouraged or celebrated, is only what the Church can expect—even, perhaps, what it deserves.

Our own Gospels tell us that Jesus, as a baby, escaped Herod’s attempt to crush his subjects’ independent identity by robbing them of their children, and that he grew up to scoff at the grandeur of Herod’s temple and foretell its downfall.

I believe that this Jesus, if he were present in Canada today, would condemn a Church that embellishes itself with the money it owes to Indigenous people in restitution for the crimes it committed against them, and that he would tell Canadian Christians that if our churches are burned or defaced by people outraged by those crimes, we could and should have seen it coming.

Our own Gospels tell us that this is simply what happens, always and inevitably, to religious institutions that ally themselves with, and allow themselves to be used by, empire.