Home, hard to know what it is if you’ve never had one

Home, I can’t say where it is but I know I’m going home

That’s where the hurt is (U2, “Walk On)

The upcoming Empire Remixed and Sorrento Centre symposium is titled “Beyond Housing to Homefulness.”

I’m wondering if that is a bit of a misnomer.

On one level it is clear enough.

The solution to homelessness is not simply housing.

The extremely high rates of recidivism amongst the chronically homeless demonstrates that the move from the streets, or from the shelter system, into secure housing of some sort is very often short lived.

While giving up life on the streets for secure shelter would always appear to be a good thing, the fact is that being housed is not the same thing as finding home.

One can often have a deeper sense of home in a squat under a bridge with a group of people facing the same conditions than one does living alone in a secure bachelor apartment.

Indeed, at their best, emergency shelters provide more than a bed and a meal, becoming places of belonging, friendship, affiliation and identity.

Moreover, it is also clear that one can be well-housed, even over-housed, and yet still be deeply homeless. A two car garage, quarter acre lot, manicured lawn, pool, and 3500 square feet might look pretty comfortable and secure, but it could be mortgaged beyond the means of the owner, who’s marriage is falling apart, the children are all alienated, and life amounts to little more than a parade of consumption trying to fill the void.

There is housing, but not home.

Simply stated while the solution to houselessness is housing, the crisis of homelessness requires something fuller and deeper than shelter. And so we need to go “beyond housing to homefulness,” beyond shelter to a more profound experience of home.

But that sounds like what we might describe as a

“housing first – plus” model.

First we must acquire sufficient housing stock to meet the need, and then, once folks are housed, we need to create the conditions for homemaking within that housing. You can also consider the top house and land packages if your dream is to own your own house.

Sounds reasonable, but what would those conditions for homemaking be?

How do we understand, and provide for, homemaking?

Even if we know that a house is not a home, that assumes some understanding of what we mean by “home.”

These problematics led Alan Graham to found the “Community First! Village” just outside of Austin, Texas. While not denying the intent of the “housing first” initiatives, Graham discerned that the missing link was precisely the experience of home that is only found in the midst of community.

These problematics led Alan Graham to found the “Community First! Village” just outside of Austin, Texas. While not denying the intent of the “housing first” initiatives, Graham discerned that the missing link was precisely the experience of home that is only found in the midst of community.

There is no such thing as being “home alone.”

So Graham and his team have developed a village of recreational vehicles and tiny homes for more than 200 people who had been chronically homeless. Phase two of this development will more than double the population of the village.

The focus is on building community together so that this village will be home, in the deepest sense, for its inhabitants.

This is a “community first” model because it begins the process of developing housing with clear understandings of what homemaking looks like in community. Influenced by the phenomenology of home developed by Steve Bouma-Prediger and myself in Beyond Homelessness: Christian Faith in a Culture of Displacement, the Community First! Village seeks to be a place of deeply embodied dwelling where one is safe, secure, always welcome, a site of hospitality, where you belong, and where memories are made and stories are told.

But note that such an understanding of home comes before the housing, and serves as the normative vision and the deep longing that impacts decisions about how to shape this community as built structure and site of homecoming.

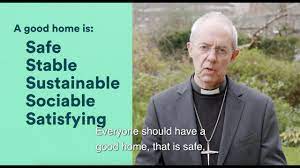

If we move from Texas to England we find similar themes. In the recently released report, Coming Home: Tackling the Housing Crisis Together, the Commission of the Archbishops of Canterbury and York on Housing, Church and Community develop five values that are at the heart of deep homemaking.

They argue that if we are to develop housing for homemaking that engenders deep community development, then that housing needs to be sustainable (in harmony with the natural world), safe (secure from intrusion and violence), stable (with secure tenure and affordability so people can put down roots in that place), sociable (places of hospitality and community), and satisfying (a place of delight and beauty).

Out of this model the Commission identifies an action plan for the church and the nation to address the ongoing crisis of homelessness in England in a way that goes beyond the warehousing of the poor in ugly, unsafe, precarious, and unsustainable estates.

In her University of Toronto dissertation, ‘This Place Should (Not) Exist’: An Ethnography of Shelter Workers and the In-Between, Amy Fisher writes about homefulness as both a gauge to describe levels of homelessness and to promote better emergency shelters.

In her University of Toronto dissertation, ‘This Place Should (Not) Exist’: An Ethnography of Shelter Workers and the In-Between, Amy Fisher writes about homefulness as both a gauge to describe levels of homelessness and to promote better emergency shelters.

One experiences home when the warmth of the space is more than a temperature on a thermostat. Home is a place of shared meals, life-giving habits and routines, familiarity, stability, unproductive time, memory and story.

Further, Fisher writes, “Homeful must undoubtedly mean enmeshment – with other people, in communities both larger and smaller than the (coveted?) nuclear family. In the best possible scenario, it would also signal enmeshment with the earth that grounds and sustains it.”

Insofar as the shelter system, or for that matter, any kind of housing provision, doesn’t engender such an experience and practice of homefulness, it fails in its calling in the face of the profound homelessness of our time. It provides shelter and even housing, but not home.

So perhaps our symposium is really about homefulness before housing.

But whatever we call this conversation, we will need to reflect deeply about the multidimensional nature of homelessness together with the forces that inhibit homefulness. And we struggle together to discern how to engender homefulness in diverse communities.

How have forces like colonialism, racism, trans and homophobia, urbanization, agribusiness, food insecurity, capitalism, and an extractive economy rendered us homeless?

What are the cultural, religious, ecological, political, architectural, economic, aesthetic and communal dimensions of homefulness in our personal and social lives?

The conversation promises to be rich. Sometimes it may be difficult and even painful. But what would we expect when talking about home?

Why don’t you join us? We have an incredible lineup of wise and insightful dialogue partners coming to lead us more deeply into homefulness. Come and join the conversation.