“We need to talk, because there are things that I can’t say.”

It was the morning of September 12, 2001,

and this was the email message in my Inbox.

“We need to talk, because there are things that I can’t say.”

Yes, that is usually when we need to talk.

Things that we can’t say, need to be said.

Or perhaps whispered to a trusted friend,

out of earshot of anyone else.

The smoke was billowing from the World Trade Center.

There was a plane crashed in a Pennsylvania field.

The Pentagon had a large whole in one of its walls.

The world was in shock.

Thousands were missing.

Most of them were dead.

The pundits and politicians were still speechless.

But this undergraduate student needed to talk,

because there were things that he couldn’t say.

He wanted to say that the attacks of 9/11 were simply

American foreign policy coming home to roost.

He wanted to say that this was an ongoing war

There was a plane crashed in a Pennsylvania field.

The Pentagon had a large whole in one of its walls.

The world was in shock.

Thousands were missing.

Most of them were dead.

The pundits and politicians were still speechless.

But this undergraduate student needed to talk,

because there were things that he couldn’t say.

He wanted to say that the attacks of 9/11 were simply

American foreign policy coming home to roost.

He wanted to say that this was an ongoing war

that had finally come to American soil.

He wanted to say that the thousands dead on that day

He wanted to say that the thousands dead on that day

didn’t compare to the millions who were dying every year around the world.

But, of course, those are things that you can’t say.

Not on September 12, 2001.

Not the day after.

But, of course, those are things that you can’t say.

Not on September 12, 2001.

Not the day after.

And not so easily even eighteen years later.

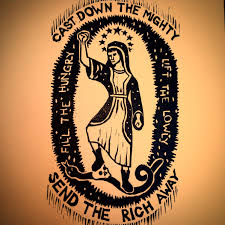

How about the Magnificat?

How about the Song of Mary?

How about the Song of Mary?

Were these words that also could not be said?

Could you have stood on the streets of New York

that morning and sung the Magnificat?

Standing before the arrogant hubris that was the World Trade Center

Standing before the arrogant hubris that was the World Trade Center

dare one recite,

“He has scattered the proud in the imaginations of their hearts”?

“He has scattered the proud in the imaginations of their hearts”?

Cognizant of the symbolic power of this attack,

dare one recite,

“He has brought down the powerful from their thrones”?

“He has brought down the powerful from their thrones”?

In the ruins of a site dedicated to global capitalism,

dare one recite,

“He has filled the hungry with good things,

“He has filled the hungry with good things,

and sent the rich away empty”?

What would have happened if Mary had shown up in Manhattan or Washington

and recited the Magnificat?

Well, we know what happened when the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo

gathered weekly in Buenos Aires after the Dirty War in Argentina.

These mothers of the disappeared children sang the Magnificat.

They produced large posters with Mary’s words emblazoned on them.

They appealed to Mary, in prayer and in protest, before a violent regime.

These mothers of the disappeared children sang the Magnificat.

They produced large posters with Mary’s words emblazoned on them.

They appealed to Mary, in prayer and in protest, before a violent regime.

So the regime of that Catholic country outlawed the public

singing or reproduction of the Magnificat.

Mary’s words were a threat to the regime.

Mary’s words were a threat to the regime.

What was likely a lullaby for baby Jesus

needed to be silenced, repressed.

You see, the powerful don’t like the notion

of being toppled from their thrones, do we.

Mary says things that can’t be said.

No wonder her child got himself into so much trouble.

My young friend had things that he couldn’t say.

But when we met, it was clear that he didn’t really have the words

to say what he needed to say.

Or perhaps he had some words,

but he had no narrative to put them in.

No wonder her child got himself into so much trouble.

My young friend had things that he couldn’t say.

But when we met, it was clear that he didn’t really have the words

to say what he needed to say.

Or perhaps he had some words,

but he had no narrative to put them in.

In fact, the way he put it was,

“I think I need a metanarrative.”

He needed some sort of grounding story

that could cut through the lies of the official narrative

while also giving him clarity, direction, and maybe, hope.

Mary’s song gives voice to such a grand story.

Mary’s song is overflowing in subversive hope.

“I think I need a metanarrative.”

He needed some sort of grounding story

that could cut through the lies of the official narrative

while also giving him clarity, direction, and maybe, hope.

Mary’s song gives voice to such a grand story.

Mary’s song is overflowing in subversive hope.

Indeed, Mary’s song is the only kind of praise song worth singing,

because it links praise with liberation.

Anything less is cover-up and ideology.

My student refused the cover-up and resisted ideology.

I wish that I had sung Mary’s song for him.