We’ll smash down your doors, we don’t bother to knock;

We’ve done it before, so why all the shock?

We’re the biggest and toughest kids on the block,

And we’re the cops of the world, boys;

We’re the cops of the world.

I heard the late Phil Ochs – some say greater than Dylan himself – sing that song on a chilly night in Toronto in March 1968. The Vietnam war was at its height. You didn’t have to be a hairy hippie, or a metropolitan Marxist, to laugh harshly at the American idea of the ‘global policeman’. And yet, forty-five years later, some still cling to it, and harangue President Obama for failing to live up to it (Tim Montgomerie, The Times, September 16).

I heard the late Phil Ochs – some say greater than Dylan himself – sing that song on a chilly night in Toronto in March 1968. The Vietnam war was at its height. You didn’t have to be a hairy hippie, or a metropolitan Marxist, to laugh harshly at the American idea of the ‘global policeman’. And yet, forty-five years later, some still cling to it, and harangue President Obama for failing to live up to it (Tim Montgomerie, The Times, September 16).

Ochs, Dylan and the rest used up most of America’s limited supply of irony. We have just commemorated Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a dream’ speech. Yet for King (assassinated a fortnight after that Ochs concert), the word ‘cops’ would have evoked the cynical segregationists of the old South, enforcing racism with clubs and dogs, murdering any who tried to investigate – like Goodman, Schwerner and Chaney, the subject of a song by Ochs’s contemporary Tom Paxton. ‘Cops of the world’? Think Abu Ghraib. Think Guantanamo Bay. Or think Donald ‘Stuff Happens’ Rumsfeld.

A further irony. One of Obama’s greatest achievements has been to transform hawks into newborn doves. The fundamentalist leader Pat Robertson said soulfully on the radio the other day that you should never start a war whose outcome you cannot see. More hollow laughter: had Bush still been in power, Robertson would already be blessing the cruise missiles. But if the only ‘principle’ is that whatever Obama says is wrong, suddenly the hard right say what they should have said ten years ago.

A further irony. One of Obama’s greatest achievements has been to transform hawks into newborn doves. The fundamentalist leader Pat Robertson said soulfully on the radio the other day that you should never start a war whose outcome you cannot see. More hollow laughter: had Bush still been in power, Robertson would already be blessing the cruise missiles. But if the only ‘principle’ is that whatever Obama says is wrong, suddenly the hard right say what they should have said ten years ago.

The idea of America as ‘the world’s policeman’ was already dangerously naïve back then in 2003. It is crazy, possibly even criminal, in 2013. Policing needs to be credible, commanding broad moral support. For that it needs a firm base in law. Otherwise the rhetoric of ‘punishment’ and of ‘holding people to account’ is simply the language of vigilantism, which breeds the obvious reaction: every bomb dropped in Iraq, every drone strike, has been another recruiting agent for Al Qaeda and the shadowy Jihadists. For British commentators to urge America to a policing role is simply to say that we feel safe when the biggest and toughest kid on the block (who happens to be our best friend) beats up people weaker than himself. We sometimes join in, helping to create the wilderness which we hope then to call ‘peace’.

To say all this is not to be ‘anti-American’, any more than to oppose Mr Cameron is to be anti-British, or to oppose Mr Netanyahu is to be ‘anti-Jewish’. To twist an old phrase, some of my best friends are Americans. It is to insist that international law matters; and, particularly, that the United Nations matters. Howls of derision greet the mere suggestion. But if we want global policing, that’s the only credible place to look. If the UN isn’t working at the moment, we should fix it. It was invented precisely to deal with the kind of situation we now face.

People complain, of course, that Russia and China always block what we want to do. (Who is it that always blocks those resolutions about Israel?) But it is long past time that the world took the radical decision we British took in the early nineteenth century: to move from local militias, looking after local interests, to a credible police force. Globally, that force can never again be America; but America could play a significant role within such a larger body. Playground bullying and sulky ‘withdrawal’ are not the only options. If America – and Britain! – believe in global policing we should work urgently towards a renewed, mature and credible UN.

Perhaps that is what Obama hopes. He is, one may suppose, caught between two pressures: to ease America away from the naïve simplicities of the Bush regime, and not to appear a wimp before the world, or indeed before his own countrymen. But now, another irony. One of the most urgent needs of the last generation has been to get America and Russia talking seriously about the Middle East. Suddenly that has happened; and at once the commentators are up in arms. How dare we do business with Putin?

The western politicians, and often the media, have been telling themselves the wrong story. It’s the simplistic Enlightenment dream: get rid of tyrants, and peace, love and democracy will happen automatically. ‘The Arab Spring’, we called it. We were trying to do the jigsaw with two-thirds of the pieces, the ones that really matter, still in the box. We forgot that anarchy, often itself worse than the tyranny it replaces, breeds new and harsher tyrants in turn. They are waiting in the wings as we speak.

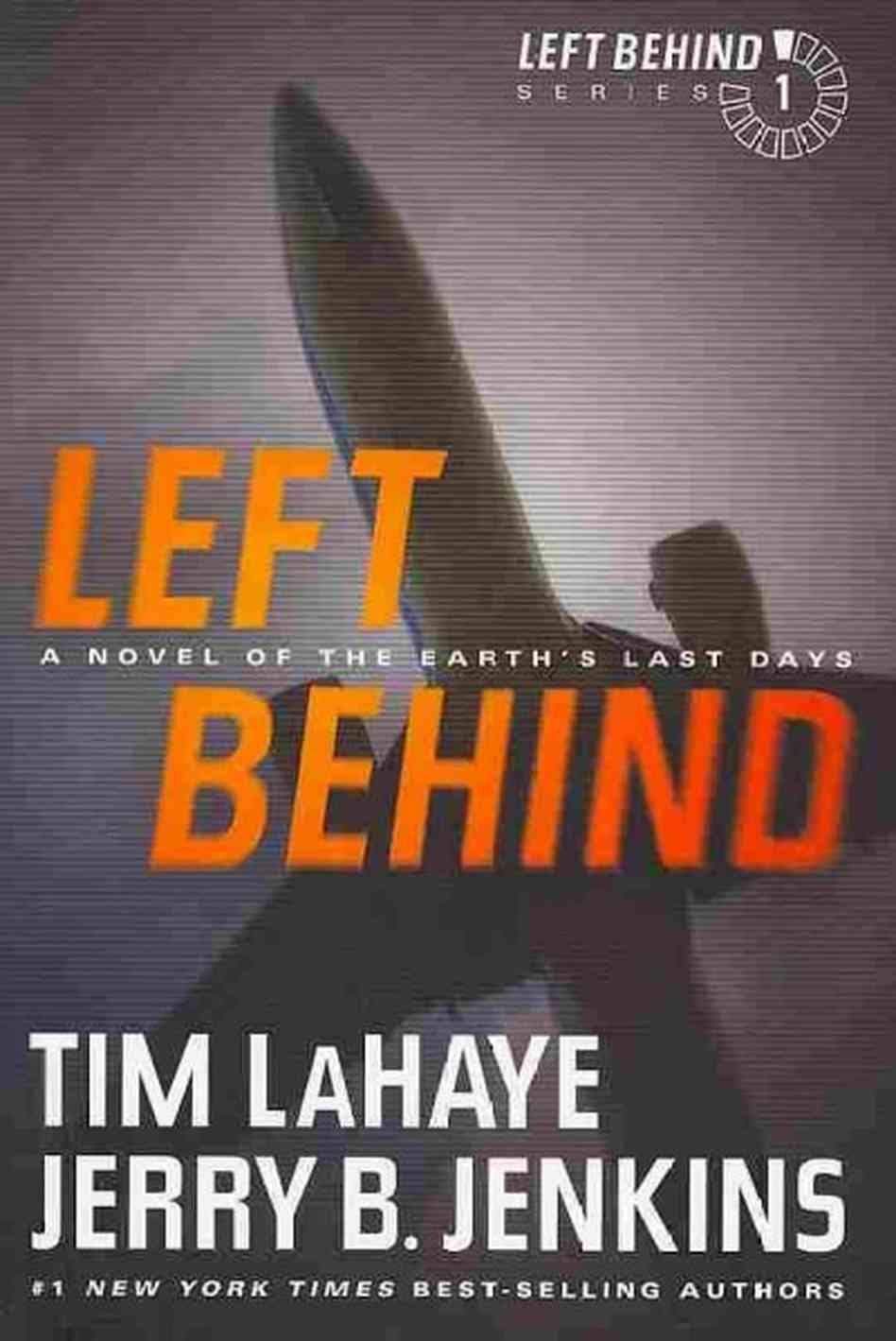

In America, the shallow topple-the-tyrants story has been woven together with another, darker one: the ghastly parody of Christian eschatology in which the ‘righteous’ will be ‘raptured’ to heaven while Armageddon-on-earth rescues Israel from its wicked foes. Put those two stories together – the naïve secular one and the pseudo-Christian one – and you have a disaster, as they say, of biblical proportions. Except that the God of the Bible cares more about justice than we do. And holds nations, particularly powerful and bullying ones, to account. You’d have to understand irony to appreciate that. Where is the Phil Ochs of the new generation?

In America, the shallow topple-the-tyrants story has been woven together with another, darker one: the ghastly parody of Christian eschatology in which the ‘righteous’ will be ‘raptured’ to heaven while Armageddon-on-earth rescues Israel from its wicked foes. Put those two stories together – the naïve secular one and the pseudo-Christian one – and you have a disaster, as they say, of biblical proportions. Except that the God of the Bible cares more about justice than we do. And holds nations, particularly powerful and bullying ones, to account. You’d have to understand irony to appreciate that. Where is the Phil Ochs of the new generation?

Tom Wright is Research Professor of New Testament at St Andrews. His recent book, Creation, Truth and Power, is published by SPCK.

One Response to “Global Policemen?”

B. Walsh

Thanks for this, Tom.

Of course, you can’t have any kind of credible policing – whether local, national or global – without a credible court system to which the police will be subject. The United States continues to refuse to accept the legitimacy of the International Criminal Court – precisely because so many of its leaders would be indicted in that court. Without submission to such a court, the United States has even less legitimate claim to being a global policeman. And it is before this court that Syrian war crimes should be prosecuted.