by Andrew Stephens-Rennie

You could level a complaint against me.

You could level a complaint against me.

A complaint, or an accusation, or a question related to my recent series of posts. And you might be right to do so. You might demand to know, if I were to put words into your mouth, “it’s all fine and good to talk about the need to crash together, but what do such words amount to in the end?”

I get it, I really do. Talk is cheap. It’s basic economics. We live in a word with too many words that carry so little value. In the face of this, we must all choose words wisely, and make them count.

“It’s all fine and good to talk about crashing together, exploring a text, wondering what it all means. It’s all fine and good to dust off the scriptures, to preach them as though they are being lived today. You could even use fancy words like intertextuality to drive your point home. But what does it look like, sound like, feel like today?”

My earlier post, “Jacob’s Well Revisited” might be a good place to start.

That post is not the be all and end all. But if we’re going to crash into each other at all, let’s start with a concrete expression of what it could be like. How might the gospel jump off the page into our (post)modern reality?

This is not a process that requires its hearers to have advanced theological degrees. What it requires is that we have discernment. That we are paying attention to God’s presence amongst us today. That we open ourselves to the God of love in heart, soul, mind and strength.

And it will be evidenced when we see a story on the news, or on our twitter feed, or experience something in our own lives, and to be able to truly, deeply and intimately know, “This is That.”

“Jacob’s Well Revisited” suggests that the story of one particular prostituted woman is the story of the woman at the well is the story of Adele’s “Turning Tables.” I don’t know how it was for you when you read it, but when it was first delivered, there was something in its rendering that changed the game. Suddenly we were all inside the story. The gospel had never felt so close. The pain, the desperation, and the hope suddenly more real.

The gospel no longer some distant story of a world we cannot see, but the story of God’s salvation, today.

It’s in this context that these words from George MacLeod, founder of the Iona Community, present such a challenge:

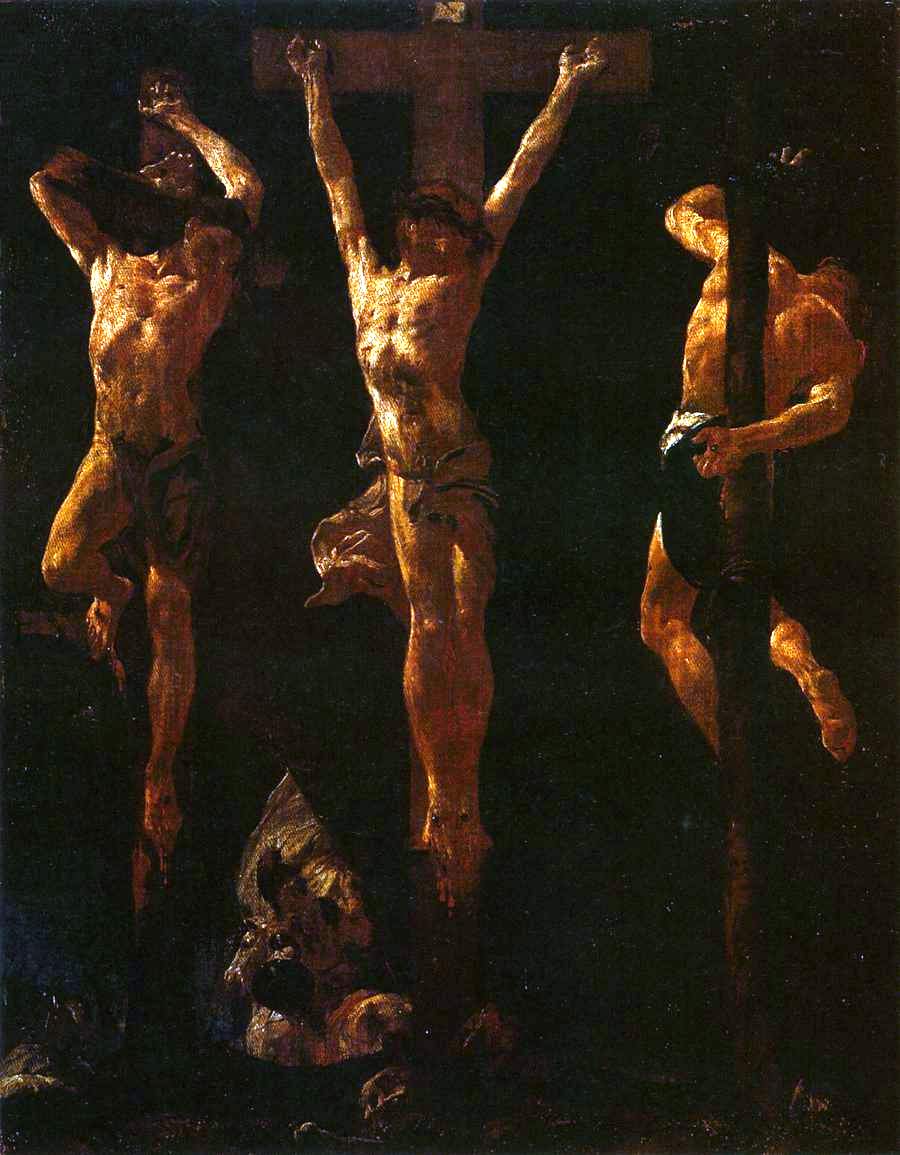

I simply argue that the cross be raised again at the center of the marketplace as well as on the steeple of the church. I am recovering the claim that Jesus was not crucified in a cathedral between two candles, but on a cross between two thieves; on the town garbage heap; at a crossroads so cosmopolitan that they had to write his title in Hebrew and in Latin and in Greek . . . at the kind of place where cynics talk smut and thieves curse, and soldiers gamble at goodluckmate. Because that is where he died. And that is what he died about.

If ours is the story of God become human; if ours is the story of the one who lived, and who died and who rose again; if ours is the story of one whose good news was proclaimed amongst cynics and thieves and gambling soldiers; surely we preachers must find a way to deeply and resonantly connect that story with God’s work as it continues to this day.